Architecture that Does not Perform

01 Observations

12-2025

A trip with the studio to Cambridge for our Christmas party resurfaced a familiar feeling. Moving through the city with its colleges, courts, libraries and streets, it became apparent how often architects expect things to perform. Buildings are read for what they signify, how clearly they express an idea or how readily they announce their intelligence. Attention is drawn to moments of emphasis. A gesture, the detail or the recognisable symbol.

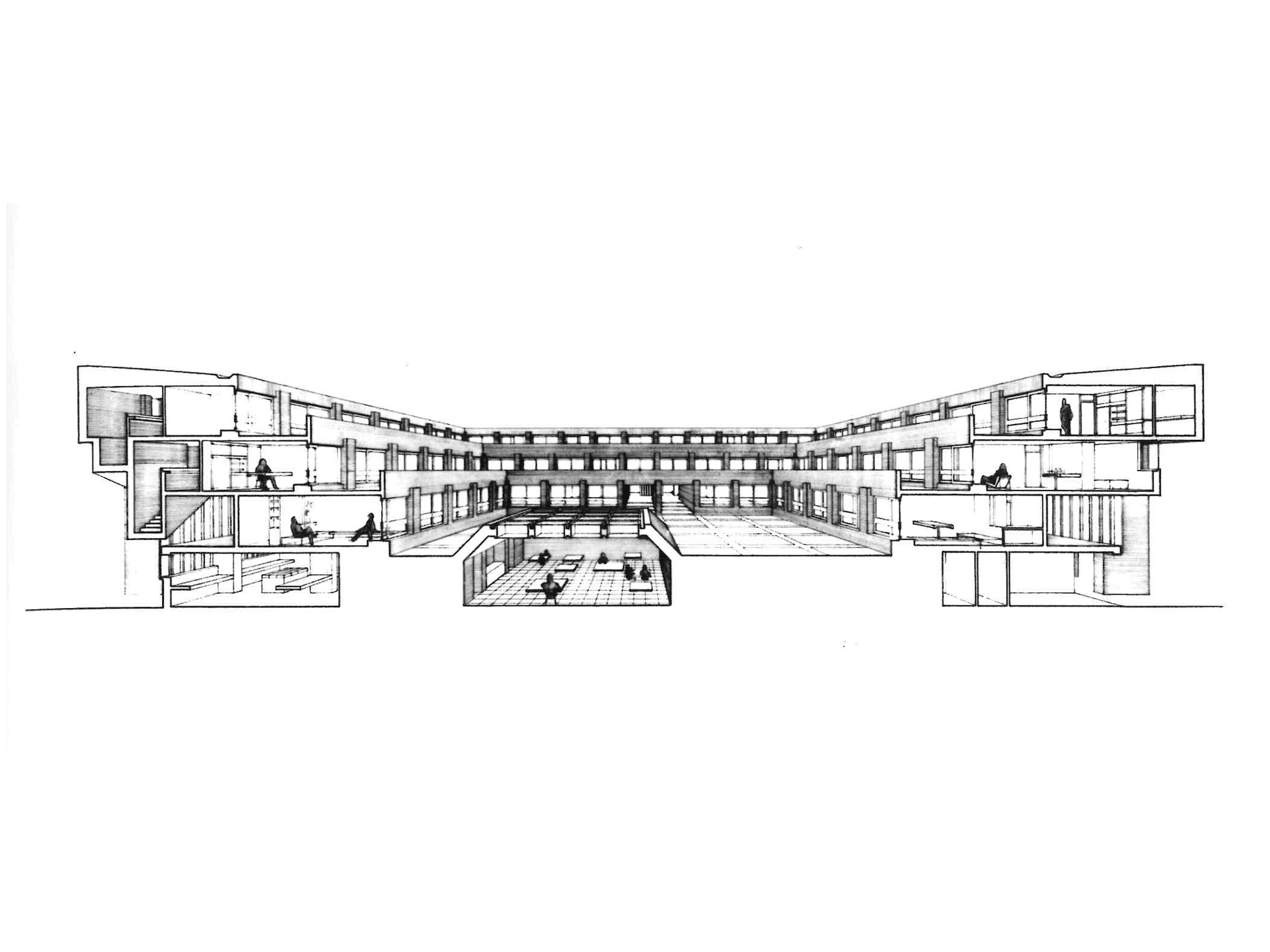

Yet many of the spaces we spent time in did something else entirely. They did not explain themselves. They did not ask to be interpreted quickly or understood through a single image. Their qualities emerged slowly through use and repetition: the depth of a threshold, the way light softened across worn stone, an assembly of simple materials stacked or arranged to celebrate the hand of its maker. These were spaces that felt accumulated rather than authored and shaped as much by time and inhabitation as by intention.

This contrast brought back a wider question about contemporary architectural culture. There is an increasing expectation that architecture should communicate immediately and explain itself. Buildings are often asked to signal their values, their sustainability, even their ethics before they have been occupied or allowed to settle into daily life. In this climate, architecture is judged quickly and often visually, through images and narratives that reward clarity of message over depth of experience.

What often gets overlooked is the slower, quieter work that architecture and some interiors can accomplish.

We are interested in buildings that do not perform in this way. Not because they lack ambition, but because they locate their ambition elsewhere. For example, ambition in use, in duration, and in the accumulated experience of inhabitation rather than in immediate legibility.

Some of the most generous spaces we know are not easily summarised. They do not announce their intentions. They unfold through repetition and familiarity. Their qualities emerge gradually: light shifting across a surface through the day, the weight of a door, the way a material softens through touch. These are not moments designed to be captured but conditions designed to be lived with.

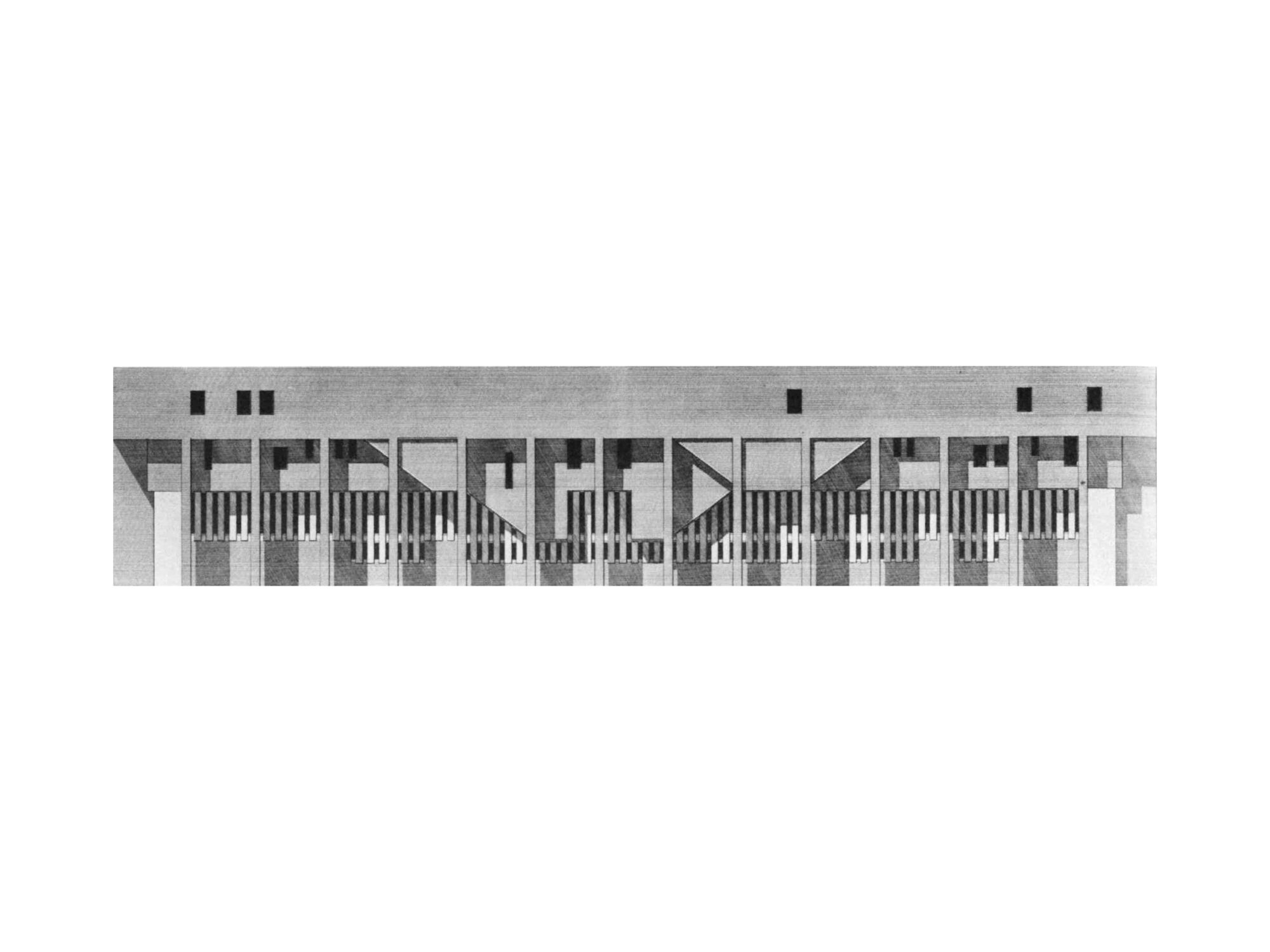

Performance-driven architecture often relies on emphasis. A form is exaggerated to signify innovation; a material is foregrounded to suggest value; a spatial move is heightened to be understood quickly. In doing so, experience is frequently flattened and the building becomes readable, but less inhabitable.

We believe architecture can be quieter than this and in doing so, more resilient.

A quiet building does not mean a neutral one. It is not an absence of decision, but the result of many decisions made carefully and for specific reasons. It is a form of discipline. Walls are thickened to slow movement rather than to display mass. Openings are positioned to regulate light and temperature rather than to frame views theatrically. Spatial sequences are calibrated to support everyday rituals rather than singular moments.

This attitude extends strongly to the way materials are used. It is also where experimentation feels most credible: not through excess or rarity, but through careful manipulation of what is already at hand.

Material value is often equated with cost or rarity. Yet some of the most convincing architectural spaces rely on materials that are ordinary, familiar, or inexpensive. Transformed through proportion, repetition or method of assembly. Here, intelligence lies in how the material is worked, combined and allowed to age.

Plaster becomes spatial when it is thickened, curved, or textured to catch light. Timber gains presence when its grain, joints, and edges are allowed to remain legible. Standard steel sections acquire weight through density and repetition rather than scale. Even industrial or off-the-shelf components can feel generous when used with care, restraint, and consistency. This approach is not about disguising economy, but about understanding it. Budgetary constraints often sharpen design judgement rather than diminish it. When resources are limited, decisions must be clearer. Each material must do more than one job: structural, spatial, atmospheric. Surface becomes a tool for transformation through polishing, burning, brushing, staining, or simply through time and use.

In this sense restraint is not a stylistic preference but an ethical position. To intervene only as much as necessary and to avoid excess not as an aesthetic gesture, but as a form of respect for the context and for the longevity of the building itself. And ultimately a respect for its users.

Restraint is frequently confused with minimalism.

We see it instead as attentiveness. An attentive building is one that listens to how people move, how they gather, how they rest and how they return. It does not attempt to choreograph behaviour precisely, but it creates conditions that support a range of uses over time. This is particularly important in domestic, civic, and restorative environments, where architecture participates directly in daily routines. In these settings, atmosphere is not decorative; it is functional. Comfort, calm, and trust are spatial qualities that emerge from proportion, material consistency and light. Not from symbolic gestures or overt references.

Architecture that does not perform also resists completion as a singular moment. It anticipates wear. It allows surfaces to be marked, materials to patinate and edges to soften. It is designed with the understanding that buildings are not finished when they are photographed, but when they have been used long enough to reveal their intentions.

In a culture driven by speed and visibility, this kind of architecture can appear reticent. It does not insist on being seen. But reticence, when deliberate is not passivity; it is confidence.

Confidence that space will do its work without explanation. Confidence that experience will outlast image. Confidence that architecture does not need to perform in order to matter.

Quiet (for us) is not a retreat from invention. It is a way of working that keeps experimentation close to making and close to materials, construction, and use. In this sense, novelty is not performed in advance, but discovered slowly as the work is lived with.

Title: Architecture that Doesn’t Perform

Year: 2025

Type: Research

Related Projects